#display museale

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

MWW Artwork of the Day (10/2/24) Hellenistic Greece (323-146 BCE) Table pedestal (Trapezophoros) with two griffins devouring a deer (4th c. BCE) Polychrome marble carving, 37 3/8 x 58 1/4 in. Polo Museale, Ascoli Satriano (Italy)

This specimin, which was unearthed from a high society grave, is considered as a masterpiece with no pre-existing equals. A trapezophore, trapezophorum or trapezophoron is the leg or pedestal of a small side table, generally in marble, and carved with winged lions or griffins set back to back, each with a single leg, which formed the support of the pedestal on either side. In Pompeii there was a fine example in the house of Cornelius Rufus, which stood behind the impluvium. These side tables were known as mensae vasariae and were used for the display of vases, lamps, and such.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

@mobiues: "i need your help. to- to bring your brother back."

To speak of a need for Loki. Who has one more profound than Thor?

’ My brother—- ‘

whose likeness is mocked up in multitudes all around, images still and moving, youth to grown, Æsirlike in all of them but for being half Laufey’s size in some. His crimes are on display. His favoured furs. He in stone, shoulder to shoulder with a carving of Thor himself.

None of these museal depictions come from Thor’s memory, only others’. What is his remains so.

Loki looms above them, pompous and horned in his mural.

’ —-is long dead, nomad. ‘

They are his only guests.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

LA VILLA DEL TEMPO – Castello dei Ronchi (Crevalcore, BO) 14.04.2024

Evento di Living History multiepoca - dai Celti alla II Guerra Mondiale - che ha riunito circa 250 Rievocatori Storici provenienti da tutta Italia. In questa edizione IMAGO ANTIQUA, specializzata nella seconda metà del XV secolo italiano, ha proposto 3 banchi didattici dedicati al corredo da tavola/cucina ed alle figure mercantili del merciaio e venditore di ceramiche. In linea con il nostro approccio, i manufatti esposti hanno incluso sia repliche di qualità museale che reperti originali provenienti dalle collezioni personali di alcuni membri.

Multi-period Living History event - from the Celts to World War II - which brought together around 250 historical re-enactors from all over Italy. In this edition IMAGO ANTIQUA, specialized in the second half of the Italian 15th century, displayed 3 educational stalls dedicated to table/kitchen equipment and the trading crafts of the haberdasher and ceramic seller. In line with our approach, the artefacts on display included both museum-quality replicas and original relics from the personal collections of some members.

Associazione Culturale IMAGO ANTIQUA - Rimini

ITALIA 1460-1490. Ricostruzione Storica, Ricerca e Didattica svolte con passione, competenza e approccio scientifico.

info@imagoantiqua www.imagoantiqua.it

#15th century#middle ages#medieval history#medievalmerchants#educationalstalls#medievalmarketplace#italy#medievalitaly

0 notes

Text

Segnalazioni

Dopo aver parlato a lezione del Cubo Garutti a Bolzano e di Una Vetrina a Roma, segnaliamo qui anche Edicola Radetzky, una struttura storica in riva alla Darsena di Milano, restaurata a partire dall’ottobre 2015 e ‘svelata’ al pubblico nel gennaio successivo.

L’Edicola “è un piccolo gioiello dei primi anni del '900, caratterizzato dalla struttura in ferro e vetro e concluso da un grande tetto a pagoda che evoca l'esotismo di quegli anni. Da luogo di vendita di quotidiani e riviste, Edicola Radetzky ritorna a vivere come centro culturale dedicato all'arte contemporanea, con un particolare rapporto tra interno ed esterno, per via delle pareti di vetro, che crea una situazione a metà tra il museo in miniatura e l'arte pubblica in dialogo con l'ambiente circostante ... una stanza delle meraviglie dedicata alla città”.

www.edicolaradetzky.it

1 note

·

View note

Quote

As in the case of traditional gothic, museum gothic often takes place at night or in exotic locales, thus creating a dreamlike atmosphere amid which what happens may well seem an expression of the protagonist’s repressed desires. Scholars fall asleep in museums, travel to obscure places, and acquire things at nightfall.

Ruth Hoberman, ‘In Quest of a Museal Aura: Turn of the Century Narratives about Museum-Displayed Objects’ in Victorian Literature and Culture, 2003, Vol. 31 No. 2

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

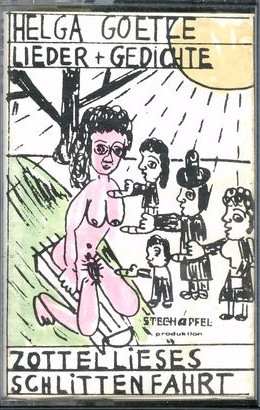

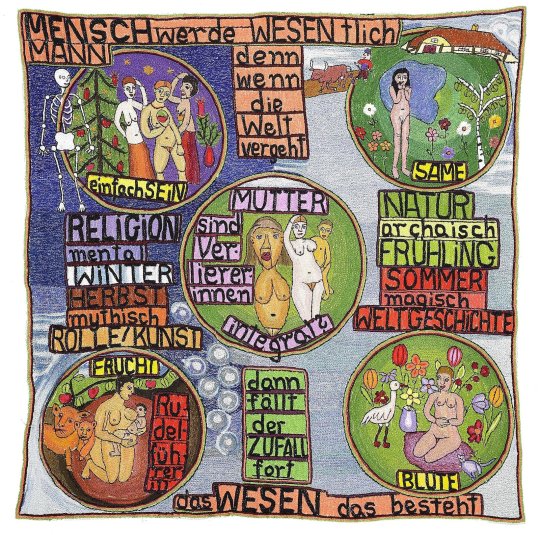

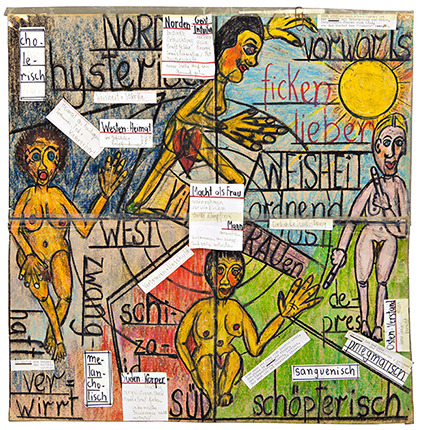

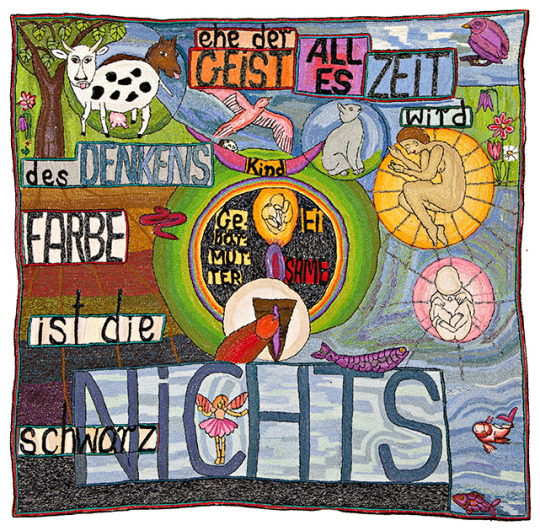

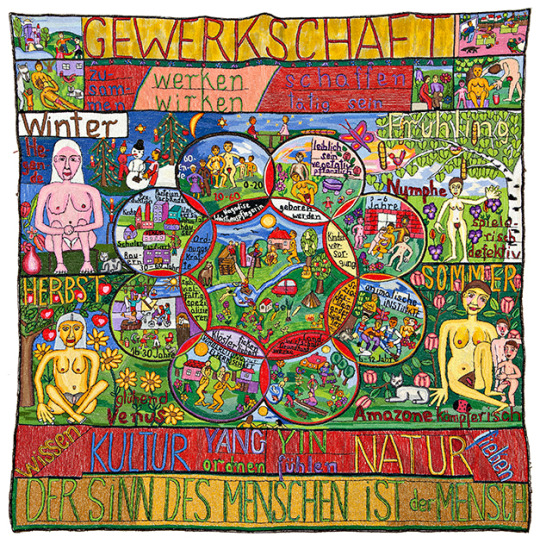

Helga Goetze

Activist and artist from Berlin

Helga Goetze (* 1922 Magdeburg, Germany, † 2008 Winsen, Germany), also known as Helga Sophia, was a German artist, writer and political activist, who lived and worked in Hamburg and Berlin. In 1972 she founded the Institute for Sex Information and published her first poetry collection Hausfrau der Nation oder Deutschlands Supersau (Housewife of the Nation or Germany’s Super Sow). Later on, Goetze kept close contact with the commune founded by the Vienna performance artist Otto Mühl and was actively associated with the Hamburg cultural centre “Fabrik”. After moving to Berlin in 1978, the artist started to maintain daily protest pickets in favour of women’s sexual liberation in front of the Technical University as well as the Berlin Gedächtniskirche. In Berlin, she also founded the “Geni(t)al University”, a gallery and open museum. Conversations with Rosa von Praunheim inspired her to make the film Rote Liebe (Red Love) in 1982. With the 1982 TV show Neue Nackte, neue Einsichten (New Nudes, New Insights), where she undressed in front of the camera, and several appearances on TV talk shows during the 1990ies, Goetze challanged the public debate around sexuality in the media. In 2000, she founded the association Metropole Mutterstadt e.V. (Metropolis Mother City) with a group of friends and in 2003, Monika A. Wojtyllo made a film about the artist, titled Sticken und Ficken (Embroidery and Fucking), which was shown at several festivals. Goetze’s works have been presented in the context of various events, readings and exhibitions, including the Museoteatro della Commenda di Prè in Genoa, Italy; the Bratislava Triennial, Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava, Slovakia; the Complesso Museale Santa Maria della Scala, Siena, Italy; and the Museum im Lagerhaus, St. Gallen, Switzerland. Since 2007, her embroideries have been part of and are on permanent display at the Collection de L’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland. Since 2014, the artist’s literary estate has been located at the archive of the Frauenforschungs-, Bildungs- und Informationszentrum Berlin (Women’s centre for research, education and information, Berlin).

source

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helga_Goetze

Documentary 1980

Spoken Word - Poetry

youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s Get Label-Conscious: Making a Museum Vice a Museum Virtue

By: Kathryn Holihan

On November 3, 2018 artist Michelle Hartney secretly hung her own labels next to prominent works by Picasso and Gauguin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York. Her self-titled “Hang and Run” performance calls for museums to “separate the art from the artist,” for both Picasso and Gauguin share exploitative and chauvinistic pasts, yet continue to be venerated by museums across the world. Quoting feminist scholar Roxanne Gay and comedian Hannah Gadsby, Hartney’s labels prompt the question: “what is the responsibility of the art institution to educate viewers and turn the presentation of an artist’s work into a teaching moment?”

Michelle Hartney’s “Hang and Run” performance: https://www.michellehartney.com/correct-art-history

Though Hartney’s website has little to say about her decision to craft guerilla museum labels, this act undoubtedly hits the museum where it hurts. Museums are label-conscious. Nearly every object on display comes paired with a label (sometimes lovingly referred to as a “tombstone”), listing basic information, including the title, artist, date, medium, and inventory number of a work. Some labels offer additional content, be it a visual description of the work, an explanation of the artistic process, or other information to assist the viewer in the act of observation. In just a few lines (because who wants to read a long museum label?), they pack a lot of punch. They should address a target audience, use accessible language, engage with the object, and, perhaps, even raise a provocative question. And though you won’t find this listed among the International Council of Museums (ICOM) standards or the V&A’s ten points to writing a gallery text, I suspect museum professionals (as museum-goers themselves) also know that in the galleries—perhaps more than we’d like to admit—our eyes dart right for the label, after only a passing glance at the artwork itself. The label is our collective museum vice, but museum professionals might make it a virtue.

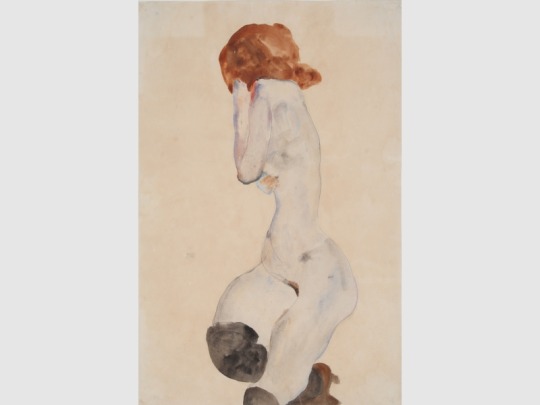

Egon Schiele, UMMA, and #MeToo

A recent exhibit at UMMA’s State Street entrance showcased a new acquisition of works by the Austrian expressionist and controversial figure, Egon Schiele. In preparation for the show, Associate Curator Laura De Becker studied Schiele’s career, including the allegations lodged against him for sexual misconduct in the early twentieth century. The vagaries surrounding the circumstances of the charges, however, far exceeded what De Becker would be able to recapitulate in a mere tombstone caption. Whereas the exhibit’s digital announcement cited Schiele’s problematic status, a conventional label listing the title, artist, date, and medium, was all that accompanied the featured works in the museum gallery. “We received a complaint about this,” De Becker reported, “and we decided to write that label,” referring to an additional text she penned in response to visitor feedback, titled “Curator Laura De Becker reflects upon Egon Schiele in the #MeToo era.”

Female Nude in Black Stockings, Egon Schiele

In this additional caption, De Becker contextualized the controversy surrounding Schiele, the moral panic prompted by his “pornographic” nudes, and his exhibition of work to a minor, for which he served a short prison sentence. De Becker further embedded Schiele’s polemical past within contemporary debates regarding consent and the treatment of women, invoking conversations reenergized by the #MeToo movement. “Museums are reevaluating their practice in displaying and discussing works by artists such as Schiele,” the new caption explained, reflexively gesturing to the ways in which artists are being “scrutinized anew” not only at UMMA, but in many other museums. In the 2018 exhibition Klimt and Schiele at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston, for example, curators revised wall texts to bring Schiele’s transgressions to light. The text, however, confined to a small series of Schiele’s early works, minimized the artist’s culpability to a specific period of his artistic career. In so doing, the MFA passed up the opportunity to, as Becker puts it, “review historical practices through the lens of evolved thinking,” be it in an ethical, moral, or legal sense.

In writing the additional caption for the Schiele exhibit at UMMA, De Becker reported, “I did not offer up any truths. This is a complicated issue, which museums are still dealing with.” Above all, she explained, “this prompted the centuries-long question: Can we disconnect art from its maker?” Using the label to prompt critical questions, De Becker embraced the politics of the label. Responding to visitorship, she mobilized the caption, not as an “objective” museal tool, but as a means to engage the public and perhaps prompt a different reading of the artwork in light of its historical past. Among a set of challenging questions contained in the new label, De Becker asked, “How do such issues affect how we look at these images now and what role does the viewer play when seeing and admiring them?”

“Race-ing through the Archive”

Shortly upon assuming her role as deputy director of curatorial affairs and curator of modern and contemporary art at the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA), Vera Grant and her colleagues began a concerted “deep drive” through UMMA’s holdings. Grant calls this ongoing venture “race-ing through the archive,” for the “elusive task of digging through the [museum] archives” is at its core an assessment of the many dimensions of race, gender, and sexuality manifest in UMMA’s encyclopedic collection. Grant’s use of the word “archive” here is deliberate, as the UMMA staff considers issues of representation—who, how, and what is being represented and to whom—from level of the artwork’s subject matter down to the language of its accompanying label. The ultimate goal, Grant attests, is to “share our own dilemmas and thoughtfulness in how we address these matters.”

Though denoted as a standard museum protocol, the act of labeling is far from simple or standardized. The label is at once liberating and limiting. “It is part of a spatial grid within which we move and interact in this world,” Grant explains. As a form of categorization, the label provides a certain sense of comfort in a complex world. “It’s almost like a form of conquering and then we can move on” she adds. But by the same hand, a label is severely limiting, as Grant notes, “that’s how labels work—they don’t tell many stories, they tell one.” A strong statement on the wall might create a miscommunication or prevent engagement across cultures. Despite the serious advantages and disadvantages of the object label, one thing is clear: it is powerful. It can elicit an array of reactions, as Grant speaks from experience about the “abundance of responses to a bit of square footage on the wall.”

One initiative stemming from “race-ing through the archive” was to address “the charged and unexamined nature of lingering object captions,” Grant reports. Take, for instance UMMA’s re-examination of the uncritical, original caption paired with the charged work J. Marion Sims: Gynecological Surgeon. Both the label and illustration lionize Sims, who stands with his arms folded at the head of the hospital scene. The illustration reproduces a racist, medical gaze, as it prompts the observer to join the ranks of other visiting surgeons who ogle the patient—an Alabama slave known only by her first name, Lucy. The caption centers less on Lucy, and more on the heroic and mythical biography of James Marion Sims, the so-called “father of gynecology.” A portion of the troubling description (below) served as the illustration’s official caption since the illustration’s accession to the University collection:

Little did James Marion Sims, M.D., (1813-1883) dream, that summer day in 1845, as he prepared to examine the slave girl, Lucy, that he was launching on an international career as a gynecologic surgeon; or that he was to raise gynecology from virtually an unknown to respected medical specialty. Nor did he realize that his crude back-yard hospital in Montgomery, Alabama, would be the forerunner of the nation's first Woman's Hospital, which Sims helped to establish in New York in 1855. Dr. Sims, who became a leader in gynecology in Europe as well as in the United States, served as president of The American Medical Association, 1875-1876; and was honored by many nations.

Contextualizing and reframing this object and text pairing, UMMA hopes to wield the power of the label to address contemporary issues, in this instance, the entanglement of violence, slavery, and medicine. Performing an academic “hang and run” of their own, Grant and her colleagues are getting label-conscious. While “race-ing through the archive,” UMMA hopes to leverage the label as a tool for grappling with artistic limitations and interrogating the museum’s own authority. Welcoming visitors into the fold, labels solicit a public response to the same questions facing museum curators: how might we use tensions manifest in the collection to reflect on the past and present and the evolution of cultural understanding? In the galleries, the visitor’s eye might still dart right to the label, but now it talks back.

Kathryn Holihan is a doctoral candidate in German Studies at the University of Michigan, where she is also a graduate of the Museum Studies Program and a participant in the Science, Technology, and Society Program. Her dissertation project Staging the Somatic: The Popular Hygiene Exhibition in Germany, 1882 1931 examines a series of hygiene exhibitions staged in twentieth-century Germany. She investigates how a group of curators, politicians, medical officials, and artists wielded public display to produce and popularize knowledge about the body. Kathryn has taught German and History courses including the original course Unsolved Mysteries: Crime, Criminology, and the Detective in Modern Germany. Kathryn is a member of a Think Tank Act conducting research on museums and public efficacy. She is also the education and curatorial assistant at the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Italian Art Exhibitions in 2019

The new year will see a wonderful array of exhibitions of Italian art going on display, with several unmissable shows coming up! Here’s a selection of some of the best to see:

First and foremost, 2019 marks the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci with a host of exhibitions and events organised across museums and galleries internationally to celebrate the multifarious and fascinating work of the master.

Leonardo da Vinci, Annunciation, around 1472, Uffizi.

Celebrations kicked off late last year at the Uffizi with Water as Microscope of Nature: Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester (until 20 January), while the paintings the Baptism of Christ, Annunciation and The Adoration of the Magi can be viewed in their new climate-controlled room.

The Louvre will be hosting a blockbuster show of Leonardo���s work this Autumn. In addition to the museum’s own exceptional holdings, including the Mona Lisa, The Virgin of the Rocks and La Belle Ferronnière, the exhibition will bring together as many of Leonardo’s extant paintings as possible, alongside drawings and sculpture, interpreted with latest findings from documentary and conservation research.

Galleries across the UK have collaborated on an unprecedented nationwide event Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing (from February 2019). 144 of the master’s most important drawings, selected from the outstanding group housed in the Royal Collection, will go on display at twelve venues across the UK. This nationwide tour will culminate in May at the Queen’s Gallery London and November in Edinburgh at The Queen's Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper for Francis I, a masterpiece in Silk and Silver (6 June-8 September 2019) will display an exceptional loan from the Vatican Museums at Leonardo’s last home where he died on 2 May 1519. Woven for Louise of Savoy and her son, the future Francis I before 1514, this is the first time since the sixteenth century that the monumental nine-metre long tapestry has been loaned. An extensive programme of events are being held across the Loire Valley, for which a dedicated website can be found here.

The major venues of Milan will be partaking in ‘Milano e Leonardo’, a city-wide programme of events held across the Castello Sforzesco, Palazzo Reale, Il Polo Museale Regionale della Lombardia, Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia, Fondazione Stelline and Biblioteca Ambrosiana. Highlights include the re-opening of the Sala delle Asse within the Castello Sforzesco, where visitors can admire Leonardo’s decorative fresco scheme for the hall, commissioned by Ludovico il Moro in 1498. The sala will host Leonardo e la Sala delle Asse tra natura, arte e scienza (16 May-18 August 2019), an examination of the iconographic and stylistic inspirations for Leonardo’s decoration of the hall, explored through drawings by the master and other Renaissance artists. At the Fondazione Stelline, L'Ultima Cena dopo Leonardo (April-June 2019) will explore the wide-ranging influence of Leonardo on contemporary artists.

In a joint venture between Florence’s Bargello and Palazzo Strozzi, the work of Leonardo’s master Andrea del Verrocchio as a painter, sculptor, goldsmith and draughtsman will be brought together for Verrocchio: Master of Leonardo (9 March 2019-14 July 2019).

While Leonardo steals the limelight this year, important retrospectives of other Italian Renaissance artists includes Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice (10 March-7 July 2019) at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, organised together with the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia with the collaboration of the Gallerie dell’Accademia. Celebrating the 500th anniversary of the birth of Jacopo Tintoretto, this is the first retrospective of the artist in North America, travelling from the Palazzo Ducale, Venice, where it showed last year.

The Hermitage’s Piero della Francesca: Monarch of Painting is on until 20 March and is the largest exhibition of the artist’s works with 11 pieces on display.

The major exponent of the Friulian Renaissance art, Giovanni Antonio de’ Sacchis, known as Il Pordenone, will be the subject of a major exhibition event to celebrate the 500th anniversary of his birth. Orchestrated as a cultural itinerary of the artist’s works throughout the Friulian region, the exhibition’s principal venue at the Galleria Pizzinato in the artist’s birthplace of Pordenone, will situate the artist’s work alongside contemporaries including Titian, Giorgione and Lorenzo Lotto.

At the Petit Palais, Paris, Luca Giordano (1634-1705): le Triomphe du Baroque Napolitain (October 2019-January 2020) presents a major retrospective devoted to the greatest master of seventeenth-century Neapolitan painting, featuring exceptional loans from the Capodimonte museum and other European venues.

The Royal Academy of Arts, London explores The Renaissance Nude (3 March-2 June 2019), charting the emergence of the nude figure as a crucial theme in European art.

Moving to the nineteenth century, the Drents Museum in Assen, Netherlands, will display Sprezzatura – Fifty Years of Italian Painting (1860-1910) (2 June- 3 November 2019) showcasing works from over forty late-nineteenth-century Italian painters such as Federico Zandomeneghi and Giovanni Segantini.

Fausto Melotti: Counterpoint (16 January 2019-7 April 2019) at the Estorick Collection, London, is the first UK retrospective of Fausto Melotti (1901-1986), a member of the Abstraction-Création movement known for his elegant, geometrical sculptures based on the principals of music and mathematics.

by Maria Alambritis

#Italian Art Society#italianart#exhibition opening#arthistory#art history#leonardo500#Leonardo da Vinci#Luca Giordano#jacopo tintoretto#Tintoretto#Andrea Verrocchio#happy new year

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

KMSKA Antwerpen fails to put together a coherent museum

In this essay I want to argue that the KMSKA fails in properly connecting the maker, the exhibitor and the viewer in the way described by Michael Baxandall in his essay ‘Exhibiting Intention: Some Preconditions of the Visual Display of Culturally Purposeful Objects’. This essay is mostly about anthropological exhibitions, but is also very applicable to the KMSKA. I also want to prove that the museum mostly focuses on the museum effect, a term coined by Svetlana Alpers in her essay ‘The Museum as a Way of Seeing’.

The first thing you notice when you enter the KMSKA is the monumental architecture. Outside you have the very classical structure reminiscent of the old Greek and Roman temples, whereas inside you are greeted with blinding white walls and floors. The KMSKA pride themselves on the intersection of old and new architecture in the different collection rooms. They also named their own staircase the ‘Stairway to Heaven’, as it is fully white and seemingly goes on until high up in the sky.

Another part of the museum that creates a long waiting line is an installation called ‘2 Conflict Paintings + Colour Method in 7 Layers’ by Boy + Eric Stappaerts. The KMSKA itself describes this long passageway (that falls right under the stairway to heaven) as a “tsunami of colours”[2]. At the end of the passageway there’s an archive of colours fitted into a cabinet, as a sort of display of colour.

The old masters part of the museum has a big empty room where projections inspired by details of paintings get shown on the walls, and seem to move around you. It was extremely disappointing that one of their projectors apparently is already broken, as a pretty big part of the wall did not have any projections on it, but the video did seem to move on to that piece of wall. It gave off the feeling that they had a room that they couldn’t adequately fill with artwork, so they decided to make it an installment.

In this way, it almost feels like the KMSKA is mainly focusing on photo opportunities to gain some free advertising on Instagram, than it is on actually creating fine museal architecture. The stairs, projection- and rainbow room get almost more attention than the artworks themselves, because they make it easier for the visitors to take an Instagram worthy picture.

The KMSKA prides themselves on their James Ensor collection, even going as far as giving the artist a few rooms all to himself. These rooms were accompanied by small ‘chambers’ where his sketches were exhibited. The Ensor exhibition raised a few questions, but the two most important ones will be discussed below.

The first is, if this part of the museum is a part you are so proud of, then why did you make the chambers so small and the pathways so annoying to follow? There were so many people inside these rooms, as it is also the logical first part of the museum to enter. This is, of course, not inherent an issue of the KSMKA, but more of too many people wanting to see the same thing, but I do feel like the display could have been different and helped somewhat. The chambers are divided into little corners where two walls are used by two television screens, but as you barely have any space to relax and read the information on the screens, it was almost useless. At the end of the Ensor labyrinth, we get a few big white halls, which are way better to appreciate the art in peace. But why was there a random freestanding wall in this room, with nothing on the back and nothing behind it? I can get doing that to make the room feel smaller than it actually is, but this wall was placed on the longest side, and didn’t even span the whole width.

My second Ensor related question is, why is some of his art exhibited among the old masters? Since when is this symbolist painter a master of old art? He was not the only one who was exhibited in the wrong time period, as the KMSKA does divide their museum in modern and old masters, but throws art of both divisions in both sections. A Bruegel was happily lounging next to a painting by Theo Van Rysselberghe. A Basquiat was put right in the middle of a few 17th century busts. The non-chronological display of paintings has been an upcoming trend in many museums, and I can understand curators choosing this approach – going for a theme instead, for example. But if you explicitly divide your building in old and modern masters, perhaps don’t mix them around inside the exhibition rooms, it just makes it look like you don’t really know what you’re doing.

And thus, a lot of this museum remains a mystery for the viewer. Why did they put these things together? Why is there an Ensor next to an old master? And – I’m never going to let this go - please explain to me why there is a camel made out of a sofa.

[1] Svetlana Alpers, The museum as a way of seeing, 26

[2] ‘With the support of the National Lottery | KMSKA’, geraadpleegd 20 december 2022, https://kmska.be/en/support-national-lottery.

[3] Baxandall, Exhibiting intention. Some preconditions of the visual display of culturally purposeful objects, 39

[4] Baxandall, Exhibiting intention, 37

0 notes

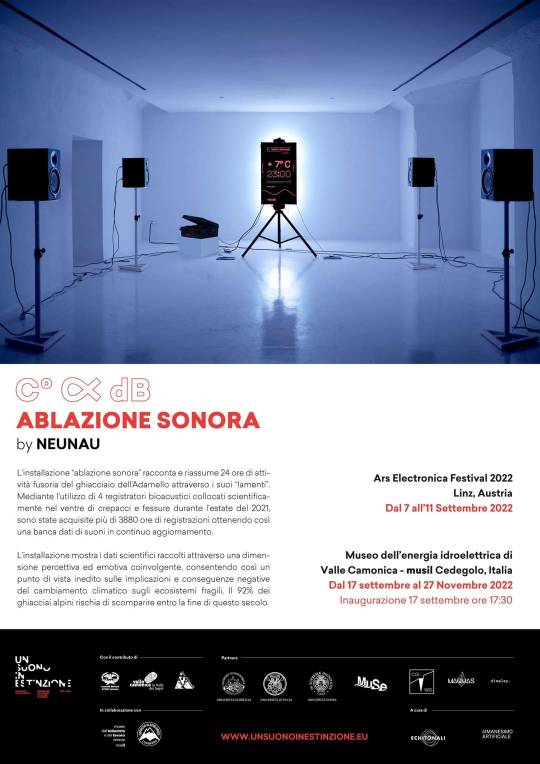

Text

L'installazione - ABLAZIONE SONORA - verrà presentata ad #ArsElectronica dal 7 all'11 Settembre e inaugurata al Musil Brescia - Sistema Museale dell'Industria e del Lavoro di #Brescia il 17 Settembre per rimanere fino al 27 Novembre.

L’installazione “ablazione sonora” racconta e riassume 24 ore di attività fusoria del ghiacciaio dell'Adamello attraverso i suoi “lamenti”. Mediante l'utilizzo di 4 registratori bioacustici collocati scientificamente nel ventre di crepacci e fessure durante l'estate del 2021 sono state acquisite più di 3880 ore di registrazioni ottenendo così una banca dati di suoni in continuo aggiornamento.

L'installazione mostra i dati scientifici raccolti attraverso una dimensione percettiva ed emotiva coinvolgente consentendo così' un punto di vista inedito sulle implicazioni e conseguenze negative del cambiamento climatico sugli ecosistemi fragili, Il 92% dei ghiacciai alpini rischia di scomparire entro la fine di questo secolo.

"ablazione sonora" è composta da un sistema audio multi canale, una sorgente luminose e da un dispositivo sul quale sono indicate le temperature, l'ora e la potenza sonora, registrate in concomitanza ai suoni che lo spettatore sentirà. I dati sono quindi posti in relazione al suono e alla luce e l'intenzione dell'artista è quella di trasformare lo spazio espositivo in un crescendo di sensazioni vissute in prima persona durante le spedizioni sul ghiacciaio.

Ablazióne s. f. [dal lat. tardo ablatio -onis, der. di ablatus, part. pass. di auferre «portare via»]. – Perdita di ghiaccio per fusione, evaporazione, sublimazione o per distacco di masse.

___________________________

Credit

Concept - NEUNAU

Coordinator - Umanesimo Artificiale

Data - Alessio Degani

Set Design - Sergio Maggioni

Graphic Design - Display.

Graphic Animation - Edoardo Massenza Milani

Lights and technology management - Ferruccio Maggioni

Foto - Paolo Sandrini

___________________________

Con il contributo di

Comunità Montana Valle Camonica, Parco Adamello, Valle Camonica Cultura.

Partner

Università degli Studi di Brescia, Università degli studi di Pavia, Università degli studi di Pisa, MUSE Trento, Umanesimo Artificiale, Comitato Glaciologico Italiano.

In collaborazione

Musil Brescia - Sistema Museale dell'Industria e del Lavoro di Brescia, SGL - Servizio Glaciologico Lombardo.

___________________________

Il progetto “un suono in estinzione” è promosso dall’Associazione Culturale ECHITONALI

Felice di aver fatto la mia parte per la realizzazione di questo fantastico progetto e ancora più orgoglioso di aver avuto la possibilità di lavorare accanto all'artista Sergio Maggioni - NEUNAU.

#neunau #unsuonoinestinzione #ghiacciaio #installazione #sounscape #studies #creativecoding #animation #graphic #animator #datavisualization #art #digital

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 7 - Role of Museums

Key Concepts of Museology, ed. André Desvallées and François Mairesse, Armand Colin, 2010, articles Collection pp. 26-28, Exhibition pp. 34-38, Mediation pp. 46-48, Museum pp.56-60, Object pp.61-64.

Collection. Defined as “a set of material or intangible objects (works, arte- facts, mentefacts, specimens, archive documents, testimonies etc.) which an individual or an establishment has assembled, classified, selected, and preserved in a safe setting and usually displays to a smaller or larger audience, according to whether the collection is public or private”. Why is it limited to having to be preserved in a “safe setting”? The author claims that “To constitute a real collection, these sets of objects must form a (relatively) coherent and meaningful whole,” I guess, a curation of works or objects that have been thoughtfully selected to convey some sort of meaning as a whole (26). This is different from a fond, which refers to a collection from a single source, without selection or intention to build a coherent whole.

The “museum phenomenon” is then closely related to a collection, as it can be described as the “institutionalization of a private collection” (27). What does the assumed materiality of a collections’ objects have to do with how “the collection is identified by the place where it is located” (28)? Are intangible collections not also identified by the places in which they were produced or are now located?

Exhibition. Defined as “the result of the action of displaying something, as well as the whole of that which is displayed, and the place where it is displayed“ (35), thus dependent on the collection, the place, and the performance/displayment.

The author argues that exhibition areas are defined not only by the “container and the contents but also by the users – visitors and museum professionals” and the resulting social interaction (35). Furthermore, exhibitions are an integral part of the museum’s general function of communication, including education and publication policies, as mediums for sensory perception by visualization, monstration, and ostention. Exhibits work as semiotics in the exhibition, which is presented as a communication process. Digital/cyber exhibition open up new possibilities of collection, ways of display, analysis, etc. but arguably hardly compete with exhibitions of real objects despite most likely having an effect on the methods currently used by museums.

Mediation. Defined as an action aimed at reconciling parties or bringing them to agreement, having the same general museum meaning as ‘interpretation’, which in the context of the museum is the mediation between the museum public and what the museum gives the public to see; “intercession, intermediate, mediator” (46).

Museum. May mean either the institution or the establishment or the place generally designed to select, study and display the material and intangible evidence of man and his environment, where the form and the functions vary over time (56). The definition given by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) is: “a museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment.” (57). The ecomuseum, virtual museum, and cyber museum are both new types of museal institutions.

The End of the Museum?, Nelson Goodman, Journal of Aesthetic Education, University of Illinois Press, Summer 1985, pp.53-62.

Goodman starts his paper with interesting analogies of what a museum likens, from a ballpark where what counts is how many people go through the gates to a hospital where it maters what happens to people while they are there to even a jailhouse with an elaborate intelligence network to capture the wanted and a security system to prevent their escape (53).

A remark that I found interesting was Goodmans explanation of why it would be impossible to run a museum like a library, one of the reasons being that “most of those who visit a museum don’t know how to see” (54) “or to see in terms of, the works there” (56). Furthermore, Goodman speaks of the effect of what we see in a museum on what we see after we leave, and in turn how what we see outside of the museum affects what we see when we return – a constant feedback loop that widens perspectives, sharpens perception, and brings out new connections and contrasts (56).

Goodman takes a critical approach in questioning the true purpose of museums, arguing that all past/present arguments for the prosperity, relaxation, and intellectualism that museums supposedly provide are “hollow” and “beside the point” (55). Yet, what then is the point? Goodman claims such arguments are “designed for those you must convince: foundations, politicians, chambers of commerce, trustees, and the public” and to “justify museums in terms of what they, on the contrary, help to justify” is a “specious challenge” (55). Who does Goodman mean with you? He continues to compare the library and the museum, claiming that the museum’s mission is most similar to the library, as fundamentally educational rather than recreational institutions.

Goodman then concludes the museum’s major mission as “making works work” (56), which is the feedback loop that happens that stimulates “inquisitive looking, sharpening perception, and raising visual intelligence” amongst other skills, in the “making and remaking of our worlds” (56). As such, ‘works work’ when they inform vision by forming or re-forming or transforming vision, not confined to visual perception but as understanding in general (57). Goodman argues that this is similar to science, and thus the differences between the arts and the sciences have been misunderstood as antagonisms when their common end is the “improvement in the comprehension and creation of the worlds we live in” (57), which I definitely agree with. Yet, the “worst imaginable conditions” under which the visitor sees works in a museum are difficult and pose three major challenges: The museum cannot instantly supply the needed experience and competence but must find ways of fostering [visitor’s] acquisition, the circumstances for viewing in a museum are at best abnormal and adverse, and the timelessness of works in a museum (58). Goodman offers suggestions to review these issues and elaborates on previous arguments.

Goodman notes that “Giving the impression that the only works worthwhile are those so rare a be confined to museums and great collections, that their works that people can own and live with – this is one of the worst effects a museum can have. And when works begin to be produced expressly for museums, we reach a stage of utter perversity” (60). I definitely agree, but how can we prevent this from happening? Is the exclusivity of works to museums not the inevitable side effect of curating great works? If museums are revered as the place of cultural and historical preservation, then is it not inevitable that people start to create art with the ultimate goal of one day seeing their work hanging in a museum?

The notion of a museum’s success being judged by its “cultural health” is also interesting (61). Goodman claims that signs that indicate “cultural health” may be “whether people are buying original works, whether commercial galleries are surviving and what they are handling, whether serious artists are becoming recognized by the public” (61).

Museums in the Digital Age, Susanna Bautista, AltaMira Press, 2013, Framing A Changing Museology In The Digital Age, pp.7-30.

Bautista starts by explaining the four major constructs that are tightly interlinked in the digital age: place, community, culture, and technology, which she thoroughly discusses throughout the book using five case studies and various scholarly concepts.

Bautista focuses on the way space and place, as the social conditions within culture is created and transformed, since museums are institutions that “somehow encompasses place, space, culture, community, public, public sphere, and society” (8) and is “ever more concerned with inclusiveness and plurality regarding their visitors and local communities” whilst striving to place themselves within a global framework (9). As “place has regained its prominence in the digital age,” as it “becomes that indeterminate point of intersection within a global network of users“ referred to as “omnilocality” (9). A transference of place, similar to migrations from peripheries to centers, is happening in the digital age: “we are where our devices are,” which in turn creates “portable communities” that use transportable technologies of communication to facilitate interpersonal connections and to make and share collective identities and culture (10). Bautista claims that technology and primacy of experience result in why place has receded for the modern museum: new digital technologies allow for new kinds of experiences, a rather continuous cycle of dependence, and museums became about experiences — “process over stasis”— and therefore less connected to place (10). Unlike a place-based approach in museums that offer experiences within their physical spaces, modern museums are now increasingly defined by the individual and less by institutional intentions. As people are becoming more aware of places as “contact zones,” Bautista echoes scholars like David Gruenewald to demonstrate the need for the educational field, like museums, to pay more attention to places: for “place-conscious education” (12). As a public sphere museums are “critical places for individual development because they reflect societal norms and values; they are places where public opinions are formed and presented, and where participation and discourse are encouraged both by peers and authority figures” (13). It is interesting to see how they have embraced the idea of the public sphere today: offering free days to ensure accessibility, free WiFi that facilitates connectedness, lectures to encourage dialogue, creating social groups for members to interact onsite and online, and soliciting comments from visitors to share publicly à rather than a public sphere it has embraced the idea of “public space”

On the topic of community, Bautista comments on the modern populist museum’s increasing concern for community as reflective of sociocultural changes, particularly in the Western world. This has happened parallel to sociopolitical developments, such as a strengthening civic engagement amongst governmental bodies, academia, and foundations for the active participation of its members and dialogue and social interaction. As “discourse is critical to place, to the public sphere, to public space” and the “approach to culture begins when the ordinary man becomes the narrator” place and community are closely related and are also both affected by changing technological means. “The ability of technology to support individual identity while concomitantly supporting communities by creating new and improved means for communication on a one-to-one basis as well as a one-to-many basis” builds “social capital and community as an active form of participation” on a global and local scale (14). Bautista names different types of communities: physical, virtual, hybrid, interpretive, ones of inquiry, ones of practice, and ones of interest. What exactly does Bautista mean by interpretive communities – is it a target audience that is differentiated through the process of interpreting work that results in differing opinions?

Bautista argues that notions of culture, the public sphere, and community overlap because they both engage discourse, conflict, and convergence on a social level. In doing so she raises interesting questions on the complexities of culture, the diverging theories (relativist vs. universalist), and the effect on the discussion of museums as cultural institutions: “If museums are cultural (and subsequently social) institutions, then how much must they reflect society’s values and concerns? Or, which culture must a museum represent, that of the nation or the community or certain subcultural groups (counterpublics) as defined by race, ethnicity, and religion?” (25). Thus, to understand museums as cultural institutions in the digital age is to critically consider how they use technologies to reflect and maintain their status, legitimacy, and authority, the “extent to which technologies support difference and dialogue, and how technology allows museums to reflect cultural norms and values in the pluralist sense” (27).

In her section on Technology and its Implications, Bautista discusses how technological advancements within museums have led to a change in community engagement, communication, and participation and an experience that is more personalized than ever. Why is it that museums have historically been more resistant to changing their practices? Bautista concludes that museums in the digital age must resolve their position on what constitutes “museum culture” and how that culture determines their usage of technology (29).

0 notes

Photo

MWW Artwork of the Day (8/19/20) Hellenistic Greece (323-146 BCE) Table pedestal (Trapezophoros) with two griffins devouring a deer (4th c. BCE) Polychrome marble carving, 37 3/8 x 58 1/4 in. Polo Museale, Ascoli Satriano (Italy)

This specimin, which was unearthed from a high society grave, is considered as a masterpiece with no pre-existing equals.

A trapezophore, trapezophorum or trapezophoron is the leg or pedestal of a small side table, generally in marble, and carved with winged lions or griffins set back to back, each with a single leg, which formed the support of the pedestal on either side. In Pompeii there was a fine example in the house of Cornelius Rufus, which stood behind the impluvium. These side tables were known as mensae vasariae and were used for the display of vases, lamps, and such. Sometimes they were supported on four legs, the example at Pompeii (of which the museums at Naples and Rome contain many varieties) had two supports only, one at each end of the table. The term is also applied to a single leg with lion's head, breast and forepaws, which formed the front support of a throne or chair. (Wikipedia extract)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Cutaneous anthrax, typical aspect of a malignant pustule. (Museal collection Coriolan Tataru, © Regional Emergency Hospital Cluj-Napoca. With friendly permission)

European dermatological wax sculpture made between 1923 and 1928.

I am inspired by the sickly pastels that the artist has depicted the horrific wounds that such a small bacteria can cause and the bulbous nature of these wounds. The deep reds and blacks in juxtaposition with the light pinks and greens paints a terrifying picture.

On outer manifestation of an inner world... can be used as a clinical tool for clinicians. I feel like my model, which will display the inner world behind this clinical picture will serve more educational purposes to enable a deeper understanding of what makes anthrax so powerful.

“Fig. 3 Cutaneous Anthrax, Typical Aspect of a Malignant Pustule....” ResearchGate. Accessed October 10, 2019. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Cutaneous-anthrax-typical-aspect-of-a-malignant-pustule-Museal-collection-Coriolan_fig3_316501680.

0 notes

Photo

Finalmente è arrivato il grande giorno: stasera alle ore 17.30 verrà inaugurata la nuova sede del #Museo di #storia #naturale Aquilegia a Masullas, il più grande della #Sardegna! 10.000 reperti di cui 3.000 in esposizione a rotazione che raccontano l' #evoluzione della nostra Isola e degli eventi geologici e biologici che nei milioni di anni hanno portato alla sua conformazione attuale e alla sua straordinaria #biodiversità. Attraverso #minerali e #fossili, provenienti dalle varie aree del #ParcoGeominerario della #Sardegna e del #mondo, la collezione di conchiglie e la collezione faunistica con #animali sardi e non solo, si viaggia alla #scoperta della storia della nostra #terra. Il Museo Aquilegia con il #GeoMuseoMonteArci e il #Giardino #Botanico, Masullas si appresta a fare vita ad un polo museale e #scientifico per lo studio delle #scienzenaturali #geologiche unico in Sardegna! Per info e prenotazioni potete contattare 3333544271 e 3201184545. 💎🌷🐚Finally the big day has arrived: tonight at 17.30 the new headquarters of the #Museum of #natural #history Aquilegia will be inaugurated in Masullas, the largest in #Sardinia! 10,000 specimens of which 3,000 on display in rotation that tell the #evolution of our #Island and of the #geological and #biological events that over the millions of years have led to its current conformation and its extraordinary #biodiversity. Through #minerals and #fossils, coming from the various areas of the #GeomineraryPark of Sardinia and the #world, the collection of #shells and the #fauna collection with Sardinian #animals and not only, we travel to #discover the history of our land. The Aquilegia Museum with the Monte Arci Geo-Museum and the #Botanical #Garden, Masullas is preparing to create a #scientific center for the study of #natural and #geological #sciences unique in Sardinia! For info and reservations you can contact 3333544271 and 3201184545. #aquilegia #masullas #museodistorianaturale #terrasarda #sardegna #sardinia #sardegnapuntoradio (presso Masullas) https://www.instagram.com/p/BvD-5MRjqkf/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1quluwb8l16qx

#museo#storia#naturale#sardegna#evoluzione#biodiversità#minerali#fossili#parcogeominerario#mondo#animali#scoperta#terra#geomuseomontearci#giardino#botanico#scientifico#scienzenaturali#geologiche#museum#natural#history#sardinia#evolution#island#geological#biological#biodiversity#minerals#fossils

0 notes

Text

Lezione del 23 marzo 2017

La lezione è iniziata esaminando l’indice del volume Sculpture and Vitrine a cura di John Welchman (Routledge 2013), una raccolta di saggi in cui vengono analizzati il ruolo e la fortuna della vetrina nel display espositivo, dalle Wunderkammern all’architettura moderna del Crystal Palace (1851) fino alle esperienze artistiche contemporanee. I temi della vetrina e della trasparenza sono stati ripresi alla fine della lezione a proposito del libro di Riccardo Donati Critica della trasparenza (Rosenberg & Sellier 2016), tra le letture segnalate in bibliografia.

Il volume ci è servito da spunto per introdurre il Cubo Garutti, opera realizzata nel 2003 dall’artista Alberto Garutti nel quartiere Don Bosco di Bolzano. Il “Piccolo Museion”, come viene anche chiamato, è una sorta di sede distaccata del Museion che prevede l’esposizione a rotazione di opere della collezione per avvicinarle a un pubblico generalmente lontano dallo spazio del museo.

ph. www.museion.it/collezione/cubo-garutti

A Roma (in via del Consolato 12) nel 2013 è stata aperta Una Vetrina: uno spazio “ridotto al raggio critico di visione di una vetrina” - appunto - dove “tutto ciò che accade e viene accolto nella vetrina è la sua arte ed è già il suo museo”.

ph. www.fondazionemaxxi.it

Per approfondire: Monsieur Bovary incontra Mr Dalloway in una vetrina, l’articolo di Antonella Sbrilli su Alfabeta2.

Nella seconda parte della lezione abbiamo analizzato in parallelo la mostra The Art of Assemblage al MoMA di New York nel 1961 e il libro Il pensiero selvaggio di Claude Lévi-Strauss pubblicato nel 1962, nel quale l’antropologo francese discute il concetto di bricoleur.

1 note

·

View note

Text

sede: Museo Civico Medievale (Bologna).

Invitato a confrontarsi con un contesto in cui la lacunosità di alcuni reperti di epoca medievale costituisce un principio fondante per l’allestimento espositivo, Genchi sceglie di posare il proprio sguardo non su ciò che sopravvive come testimonianza frammentaria del passato, bensì sulla memoria attiva di ciò che appare nella sua assenza a causa del disfacimento della storia. I danneggiamenti e i vuoti generati da terremoti, spoliazioni e cancellazioni, vengono interpretati dall’artista come segnali di un conflitto tra ricerca di eternità e consunzione del quotidiano, per essere trasformati in fenomeni visivi: oggetti dello sguardo che si aggiungono a quelli esposti all’interno del display museale. L’intervento concepito da Genchi si insinua infatti nelle profondità delle opere non per sondarne l’intenzione semantica, ma per indagarne le parti mancanti che ne compromettono una rappresentazione formale compiuta, e proprio per questo, continuano a echeggiare per lunghe distanze temporali la necessità di trasmissione della propria percezione, oltre la soglia di ciò che è accessibile all’occhio. Lungi dall’inscriversi nella tradizione dell’estetica del frammento che intende ricostruire una formalizzazione simbolica degli artefatti lacunosi attraverso la loro integrazione e completamento, il processo creativo di Genchi trova negli spazi che si aprono dalla coesistenza antagonista di visibile e invisibile il varco per costruire una fruizione inedita del Museo Civico Medievale. L’artista interagisce infatti con le sue collezioni e i suoi spazi architettonici attraverso un percorso di installazioni poligonali, in alcuni casi delimitate da cornici in alluminio anodizzato argenteo, fissate in sospensione alle pareti da tiranti, che affiorano come espressioni mediate di un tempo trascorso non più visibile attraversando sei sale del museo, tra piano interrato, piano terra e primo piano come un fluido dispositivo di compatta coerenza formale. In questa trama di segnali visivi costruita per attivare uno stato di attenzione, Genchi affronta il rapporto con l’antico nella consapevolezza che l’allestimento è forma architettonica di assoluta sostanza scegliendo, di sala in sala, di indirizzare lo sguardo dello spettatore su alcuni importanti pezzi del patrimonio conservativo, in una relazione che esalta la densità spaziale tra opere e contesto. E il caso della grande statua di Bonifacio VIII in lastre di rame dorato, eseguita all’inizio del XIV secolo da Manno Bandini da Siena collocata nella sala VII, del bassorilievo riproducente Apollo che suona la cetra, di probabile fattura quattro-cinquecentesca veneziana, esposta nella sala XV, oppure del trittico con Madonna, Bambino, Angeli e Santi di Jacopo della Quercia visibile nella sala XII. Ogni opera realizzata dall’artista riproduce un modulo di varianti geometriche e trova un suo luogo preciso di collocazione in un punto che stabilisce dinamiche di dilatazione o contrazione della tensione volumetrica delle sale espositive, stimolando la scoperta di una nuova visione dello spazio museale. Il percorso di visita scandito dal ritmo complessivo degli interventi viene così ad acquistare l’importanza di un’azione significante nell’incontro del pubblico con le opere. Raccogli la cosa nell’occhio convoca lo sguardo dello spettatore verso l’ineluttabile interrogazione sul compiersi e rinnovarsi del senso che il vuoto della forma, nello spazio e nel tempo, pone incessantemente.

Con queste parole Martino Genchi spiega la scelta del titolo: “Raccogli la cosa nell’occhio è il titolo di un racconto che avrei voluto scrivere. Parla di un uomo ordinato che perde un oggetto a cui tiene molto. Sempre più spesso ha l’impressione di scorgere l’oggetto in questione al limite del suo campo visivo, gli sembra di vederlo appoggiato da qualche parte, sul mobile alle sue spalle o riflesso in un vetro. Ma quando si gira non c’è niente. Mano a mano che il racconto procede il protagonista si accorge che l’oggetto perduto si trova in realtà proprio nel suo occhio, in una zona periferica a cui riesce ad accedere solamente sforzandosi di guardare il più possibile lateralmente. Con dolore e fatica ruota gli occhi sempre più a fondo, ogni volta più indietro per indagare questo spazio, rendendosi progressivamente conto che c’è qualcos’altro: altri oggetti persi negli anni da lui – ma non solo. Poco a poco gli si delinea un paesaggio di relitti e macerie, una specie di città abbandonata piena di cose, raccolte e disposte evidentemente da qualcuno che non è lui”.

L’intervento è accompagnato dal contributo critico di Claudio Musso.

Il progetto rientra nella sezione Art City Polis della quinta edizione di Art City Bologna (27 – 28 – 29 gennaio 2017).

#gallery-0-4 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 25%; } #gallery-0-4 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Martino Genchi. Raccogli la cosa nell'occhio sede: Museo Civico Medievale (Bologna). Invitato a confrontarsi con un contesto in cui la lacunosità di alcuni reperti di epoca medievale costituisce un principio fondante per l'allestimento espositivo, Genchi sceglie di posare il proprio sguardo non su ciò che sopravvive come testimonianza frammentaria del passato, bensì sulla memoria attiva di ciò che appare nella sua assenza a causa del disfacimento della storia.

0 notes